"Most [African] countries are caught in what I have elsewhere called the fiscal policy trilemma": Abebe Aemro Selassie, IMF's African Department

I will start by pleading mea culpa for two sins I am about to commit:

Ø Only covering sub-Saharan rather than the whole Continent; and

Ø For doing so in a very aggregated way. For what makes Africa rather fascinating is its incredible heterogeneity—from its peoples’ genetic pool to its topography, music, language, and indeed economic circumstances.

To the subject at hand. This chart captures nicely the trajectory of GDP per capita in sub-Saharan Africa’s since 1960. Periods of strong improvements in living standards (1970s); periods of sharp regression in income (1980s); and the 2000 through 2015 or so period—billed Africa Rising—when once again income growth accelerated quite a bit. As Lant Pritchett once characterized it.

Again, I want to stress that there is quite a lot of variation around this average path. Quite a lot.

For the economists in the room in particular but really everybody interested in Africa claiming its rightful economic place: understanding the factors that cause economic shrinkages, as much as rapid growth, is sine qua non.

As economic historians remind us this was also much the case of currently advanced countries prior to the 20th century, when growing and shrinking occurred in roughly equal proportions—as Broadberry, of Nuffield College here, and Gardner (2019)[1] argued very compellingly. But in this century, advanced countries have largely avoided sustained shrinkages…

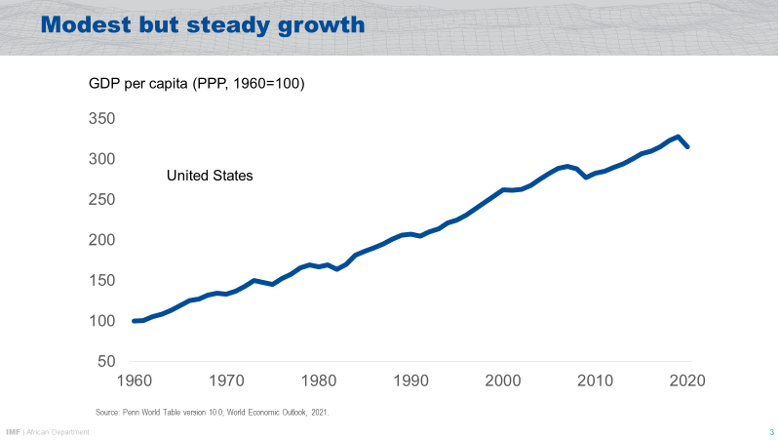

This chart demonstrates what I am getting at. It shows the evolution of per capita income for the United Sates as the representative advanced country case.

Over the same period I showed earlier, growth has been characterized by steady (around 2 percent on average) but steady growth. To be sure there are business cycles, but short-lived ones and without reversing income gains much.

This begs the question as to what might explains the volatility of growth in Africa?

To a first approximation, growth downturns in the region coincide with large exogenous shocks. Take the downturn in growth circa 1980. It had a great deal to do with downturn in commodity prices that happened then, as advanced countries slipped into recession. Coupled with ineffective and/or problematic policies and political problems (often related to the difficult economic circumstances), it tended to cause growth to slump for years on end.

1980-1995

The preceding is all a set up for the central point of my remarks today: the region is once again at one of those pivotal inflexion points in its economic trajectory. The COVID-19 pandemic, as elsewhere, has caused an acute health and economic crisis.

With limited resources, African countries have not been able to cushion the effects of the crisis on their people. This is in sharp contrast to the hugely supportive monetary and fiscal policies that advanced countries were able to deploy!

The effect has been

a dangerous divergence in pace of recovery from recession (1/3 of SSA countries will not be back at their 2019 level of GDP by 2025; most advanced countries will be there this year—35 out of 39 advanced economies’ GDP per capita in 2021 will be higher than 2019 (or 90% of AEs).

Ø unless countered by a combination of bold and transformative policies and support from the international community, another lost decade could be afoot ….

But this is not preordained, and I am very bullish about the prospects for our Continent.

The first and perhaps most important reason for my optimism is the more robust development indicators than in the past. Sub-Saharan Africa is a much-changed from 1980 or 1990.

It goes without saying that poverty remains unbearably high, the fruits of strong growth in some countries have accrued disproportionately to the better off, and far too many people are still impacted by conflict.

But there has also been much progress and transformation. And, I am not talking about skin-deep changes such as shiny new buildings or a better skyline, but fundamental progress that has shifted the opportunity set of a generation.

Take political developments: an increasing number of countries have moved from unconstrained leaders to systems with more checks and balances. In some cases, we are home to some of the world’s most boisterous democracies. The sharp improvement in life-expectancy is another example of improvements.

This much-improved starting conditions should help our countries be more resilient this time round subject to emerging challenges we face being tackled effectively and forcefully.

And I want to touch on three such challenges briefly next—the ones that I think are really key.

Improving economic resilience and improving development outcomes further will require countries to deepen the social contract. Most countries are caught in what I have elsewhere called the fiscal policy trilemma:

Ø Huge pressures to increase to spending—to address long-standing infrastructure and social spending needs

Ø High public debt levels making borrowing to address spending pressures difficult; and

Ø Resistance to higher taxes.

This tension is not new, but the pandemic induced economic strains have made the tension more acute.

The progress that our countries make in strengthening the social contract, by governments becoming more accountable and their citizens trusting them enough to pay more taxes, will have a huge bearing on how countries fare.

The pandemic has illustrated the value of digitalization but is also a stark reminder of the remaining digital divide.

While telework arrangements have allowed businesses to continue partial operations in many countries, the switch to telework has been less pronounced in sub?Saharan Africa, mainly because of less reliable internet connectivity and electricity supply.

Emerging from the pandemic will depend on integrating digital strategies within each country’s broader development agenda.

Climate change has highly uneven effects across the globe. It is a global threat to which SSA contributed little but will bear most of the adverse consequences. This chart shows the expected effects on economic output around the world of a 1 degree centigrade increase in temperature globally.

Given the constraints of many SSA countries and the negative spillovers from vulnerable countries, the international community must play a key role in supporting these countries’ efforts to cope with climate change.