Trade within Africa will help maintain food security through the pandemic, FAO says

NAIROBI — Africa, a continent that depends heavily on food imports, should strengthen its interregional trade to maintain food security throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, said Maximo Torero, chief economist and assistant director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, during a webinar on Wednesday.

“We're concerned about the effect of potential export bans as countries start to look after themselves first.”

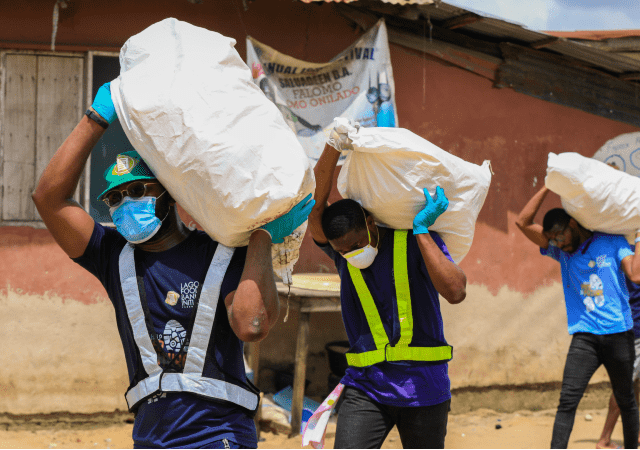

— Amar Ali, CEO, Africa Improved FoodsThe food security implications of the COVID-19 pandemic is a “crisis within crisis,” said Abebe Haile-Gabriel, assistant director-general and regional representative for Africa at FAO, noting the importance of prioritizing protection of the food supply chain as a key part of the response to COVID-19.

While there are currently no supply shocks in availability, there are starting to be shocks in terms of movement which could impact Africa’s ability to import and export food, and “there are seemingly countless ways the food systems will be tested and strained in the coming weeks and months,” Torero said.

Globally, Africa’s top trading partners of agriculture products, including partners in Europe, are also facing financial strains from lockdowns, which could curb demand for imports, turning them into less reliable trade partners for African countries, Torero said.

To hedge against these threats to both imports and exports, African nations should strengthen trade across the continent, he said.

These efforts are already underway.

Last year, the member states of the African Union created the African Continental Free Trade Area, aimed at creating a single market for goods and services, as well as to promote the movement of people across borders. Its implementation is expected to take years. But this process should be hastened in response to the pandemic, Torero said.

“We believe inter-regional trade could be a very good option today, given that the global trade, and the countries where you used to trade or export will be severely affected in the next 12, 16, or 18 months,” he told webinar participants.

Top agricultural imports to Africa include wheat, palm oil, maize, sugar, rice, milk, and soybean oil, according to UN Comtrade, the United Nations International Trade Statistics Database. Top agriculture exporters to Africa include Brazil, Russia, Argentina, France, India, United States, Indonesia, China, Malaysia, and Ukraine. Of those, both India and the U.S. are currently a concern, Torero said, with delays of shipments from India already occurring.

Top export agricultural products from Africa include maize, bananas, cheese, soybean oil, sugar, cigarettes, fowl, and shrimp. Top importers of African agricultural products include the Netherlands, France, Spain, U.S., Germany, China, U.K., India, Italy, and Belgium — all countries that have been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the barriers to interregional trade is the poor infrastructure linking countries. While that is unlikely to change in the coming months, there are other steps countries can take to reduce trade restrictions, Torero said, such as reducing import tariffs and temporarily reducing value-added taxes, as well as other taxes.

There will be a temptation for countries to institute export bans, he said, but that should be avoided. If country currencies devalue as their economies are hit by the pandemic, it can create incentives for export companies to move commodities out of the country quickly, rather than supply domestic markets.

“We're concerned about the effect of potential export bans as countries start to look after themselves first,” said Amar Ali, CEO at Africa Improved Foods. “Keeping those borders open and the free flow of goods across those borders is really, really important for us.”

Landlocked countries suffer first when borders close, said Vanessa Adams, vice president of strategic partnerships at Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.

Countries should also avoid panic buying staple commodities, such as wheat, maize, corn, soybeans, and rice, to bolster national strategic food reserves, Torero said.

Currently there are adequate global supplies of staple commodities. Because of this, the price of staples has dropped.

“If you ask me: Should we buy food for staples for reserves? It is a mistake. Because the price will be lower tomorrow,” he said. “The only thing that you will do is increase your costs and create the typical problems of storage.”

The situation is not the same for high-value commodities, such as fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish, which are labor-intensive, making them more vulnerable to lockdowns. They are also more sensitive to delays in transportation because they are perishable. These types of commodities face more challenges in the coming months, Torero said.

Within countries, there is a need to create linkages between farmers and consumers, and the need for a broad range of economic interventions to support food producing companies and prevent massive shutdowns and layoffs, said Ziad Hamoui, president of the Borderless Alliance in Ghana.

There is also a need to shift attention away from increasing production toward reducing post-harvest loss through improved storage methods, he said.

Proper storage can help farmers keep their harvest for six to 12 months, Torero said. This will also allow farmers to hold on to their crops during this period until prices recover.

There is also a concern about a drop in available financing and working capital for small and medium-sized enterprises and agro-dealers, as well as access to agricultural inputs, such as fertilizer, for farmers, Adams said.

“I'm a firm believer that a crisis is also an opportunity. We should use this crisis as an opportunity to build more resilient food systems,” she said.